Analysis: Intel’s Turnaround Strategy Faces Challenges

The U.S. semiconductor giant faces five major challenges. What are the challenges?

By Mark LaPedus

Intel is taking several major steps to bolster its semiconductor business and strengthen its bottom line, but the troubled company continues to face a multitude of challenges in the market.

As part of the moves, Intel is assembling a new executive leadership team to run its semiconductor product and foundry units. The company also recently received separate investments from Japan’s Softbank and the U.S. government.

These and other moves are part of an ongoing effort to get Intel back on the right track. After years of dominating the microprocessor and other chip markets, the U.S. semiconductor giant has recently fallen on hard times amid a period of losses, layoffs, product setbacks and manufacturing miscues.

Looking to reverse those trends, Lip-Bu Tan, Intel’s new chief executive, is making a series of major moves to reshape, if not revive, the troubled company. Intel, the leader in the microprocessor business, continues to lose market share in several key segments amid stiff competition in the business. In addition, Intel Foundry Services (IFS), the company’s other main business, continues to lose money. On top of that, Intel has reported several consecutive quarterly losses.

Nonetheless, in one major move to stop the bleeding, SoftBank has made a $2 billion investment in Intel. Under the terms of the deal, announced on Aug. 18, SoftBank will pay $23 per share of Intel’s common stock, giving the Japanese company a 2% stake in Intel.

Then, on Aug. 22, the U.S. government invested $8.9 billion in Intel. The government agreed to purchase 433.3 million shares of Intel’s common stock at a price of $20.47 per share. Now, the U.S. government has a 9.9% stake in Intel.

The deals with Softbank and the government will bolster Intel’s financial position. Now, Intel is assembling a new executive team that supports its strategy to strengthen its product and foundry businesses. The changes also include the departure of a key executive. Here are the new appointments and changes at Intel:

*Michelle Johnston Holthaus, chief executive of Intel Products, will depart after more than three decades with the company.

*Kevork Kechichian has joined Intel as executive vice president and general manager of the Data Center Group (DCG). Reporting to Tan, Kechichian will lead Intel’s data center processor business. Kechichian joins Intel from Arm, where he was executive vice president of engineering.

At Intel, Kechichian assumes the leadership position at DCG from Karin Eibschitz Segal, who led the group on an interim basis, according to CRN, a trade publication. On LinkedIn, Segal is listed as co-general manager of Intel Isreal.

* Jim Johnson has been appointed senior vice president and general manager of Intel’s Client Computing Group (CCG). Johnson, who served in this role on an interim basis, is in charge of Intel’s PC processor business. Johnson will report to Tan.

*Naga Chandrasekaran, executive vice president and chief technology and operations officer of Intel Foundry, will expand his role to include Foundry Services. Chandrasekaran will continue reporting to Tan. Kevin O’Buckley continues as senior vice president and general manager of Foundry Services, reporting to Chandrasekaran. Previously, O’Buckley reported to Tan, according to CRN.

*Intel is establishing a new Central Engineering Group under Srinivasan Iyengar, a senior vice president and Fellow at the company. Iyengar, who will build a new custom silicon business, reports to Tan.

To be sure, Intel has flooded the zone with a flurry of news announcements. To summarize these announcements, Tan is implementing a bold new turnaround strategy. Since joining the company as CEO in March, Tan has taken swift actions to strengthen Intel’s financial position, drive disciplined execution in its product and foundry units, and revitalize an engineering-first culture.

It’s a critical time for Intel. It is currently undertaking a major expansion of its domestic chipmaking capacity, investing more than $100 billion to expand its U.S. sites.

But even with the funding and new executive appointments, Intel faces a number of challenges. In my assessment, here are the five main challenges:

*Regain lost processor share

*Get a foothold in AI chip market

*Fix the foundry business

*Monetize the advance packaging business

*Stay the course or go fabless

I have described each challenge in detail below.

Regain lost processor share

In terms of market share, Intel is still the leader in the processor business for both desktop PCs and notebooks. AMD, however, is gaining ground in the desktop processor market, at the expense of Intel.

Both Intel and AMD face some new competition from Arm-based processors in the desktop and notebook markets. Arm's share of the PC processor business reached 13.6% in the first quarter of 2025, up from 10.8% in the fourth quarter of 2024, according to Mercury Research and PC Gamer.

Meanwhile, for some time, Intel has also been losing market share in the x86-based processor market for servers. Generally, x86-based servers are general-purpose computers, which are used in businesses and data centers. Server processors, which are different from PC processors, are designed to handle more complex tasks. The server processor market is also a big business with higher margins.

Back in the second quarter of 2020, Intel was the leader in the server processor market with a 94.2% share, according to Mercury Research and Tom's Hardware. At the time, AMD had just 5.8% share of the market, according to Mercury Research and Tom’s Hardware.

Over time, Intel’s share has dwindled. In the second quarter of 2025, Intel’s share of the x86-based server processor market was 72.7%, compared to 27.3% for AMD, according to the firms.

Needless to say, Intel hopes to regain share. The company is banking on some new and promising products to regain its footing.

For example, at the recent Hot Chips 2025 conference, Intel presented a paper on a next-generation Xeon 6 processor for servers. The x86-based processor, codenamed Clearwater Forest, is a 288-core device based on Intel’s E-core (efficient-core) microarchitecture. A two-socket device consists of 576 cores. Intel’s E-core technology enables a high core density processor with power efficiency in mind.

Clearwater Forest also features a chiplet architecture, including a group of chips based on the company’s new 18A process technology. For this 3D-like device, Intel stacks 12 CPU chiplets, three base chiplets and two I/O chiplets all on a base die. The 12 CPU chiplets are manufactured using Intel’s 18A process. Based on a 3nm process, the three base chiplets consist of memory controllers and I/O. The two I/O chiplets are based on a 7nm process.

Clearwater Forest is due out in 2026. Still, it's unclear if Intel can regain any share in the server processor market. AMD has the momentum here, making life difficult for Intel.

Get a foothold in AI chip market

In the 1980s, Intel launched a series of x86-based processors for the emerging PC market. Over time, the PC market took off. Intel rode the PC wave, becoming a powerhouse in the PC chip market.

Then, in the 2000s, the cellphone market skyrocketed. Intel tried but failed to get a foothold in the cellphone processor business. It missed the market window.

Fast forward. As it stands today, Intel is in danger of missing the AI market window. Today, Intel sells an AI accelerator chip called Gaudi 3. IBM has adopted Intel’s Gaudi 3 for its cloud service customers. But beyond IBM, Intel has garnered little or no traction for the AI chip.

For AI, Intel’s last hope is perhaps a next-generation Gaudi AI accelerator, codenamed Jaguar Shores. Intel plans to use SK Hynix’ HBM4 memory devices with Jaguar Shores. It’s unclear when Jaguar Shores will appear.

To be sure, hyperscalers and server vendors would like to have an alternative to Nvidia, the dominant supplier of AI chips in the market. There are plenty of alternatives in the market. AMD and others are shipping AI chips. In fact, there are over 100 entities competing in the AI processor market alone.

So, is there room for Intel in the AI chip space? There is room, that is, if Jaguar Shores is competitive, if not superior, to Nvidia’s GPUs. If Jaguar Shores is a “me-too” product, Intel will end up becoming a niche player in a big business. Worse, it could miss the market window.

Before that happens, Intel may be forced to acquire an AI chip company just to get a foothold in the business. That also doesn’t ensure success for Intel, however.

Fix the foundry business

In the semiconductor industry, Intel is called an integrated device manufacturer (IDM), meaning the company is capable of doing nearly everything in-house. First, Intel designs its own processors and other chip lines. Then, the company can make these chips within its own manufacturing facilities, which are called fabs. And Intel also has several internal IC-packaging facilities. So, it’s capable of assembling its own chips into IC packages.

For years, Intel was the undisputed leader in semiconductor manufacturing technology, giving the company a competitive edge in the microprocessor and other chip markets.

Meanwhile, over the years, Intel has entered into several new chip markets in effort to expand beyond its processor business. For example, in 2010, Intel entered the foundry business. Foundry vendors manufacture chips for other companies. TSMC, Samsung, SMIC, UMC, GlobalFoundries and others compete in the foundry business.

Soon after it entered the foundry business, Intel exited the market. Then, in 2018, Intel stumbled and lost its leadership position in semiconductor manufacturing technology. Both TSMC and Samsung passed Intel in terms of manufacturing technology.

Looking to get the company back on track, Intel hired Pat Gelsinger, a former Intel technologist, as its new CEO in 2021. Under Gelsinger’s leadership, Intel reentered the foundry business in 2021. At the time, the company also announced several new fab projects. It also announced plans to develop five new semiconductor manufacturing processes in four years, including a technology called 18A.

At the time,18A represented Intel’s most advanced process. With 18A, Intel hoped to regain the leadership position in manufacturing technology. 18A incorporates two major innovations—a new gate-all-around (GAA) transistor technology and a backside power delivery network.

Intel’s move to reenter leading-edge foundry business made sense for two main reasons. First, the majority of leading-edge logic chips were (and still are) made in Taiwan by foundry giant TSMC. Second, the U.S. was (and still is) behind in logic technology.

So, for national security purposes, the U.S. needs a domestic leading-edge chip-manufacturing capability. And Intel is the only U.S.-based chipmaker capable of manufacturing leading-edge chips. Plus, with the help from its leading-edge fabs, Intel could once again gain a competitive edge in its processor business.

Under Gelsinger, though, Intel struggled. Gelsinger was eventually forced out, and in March 2025, he was replaced by Tan.

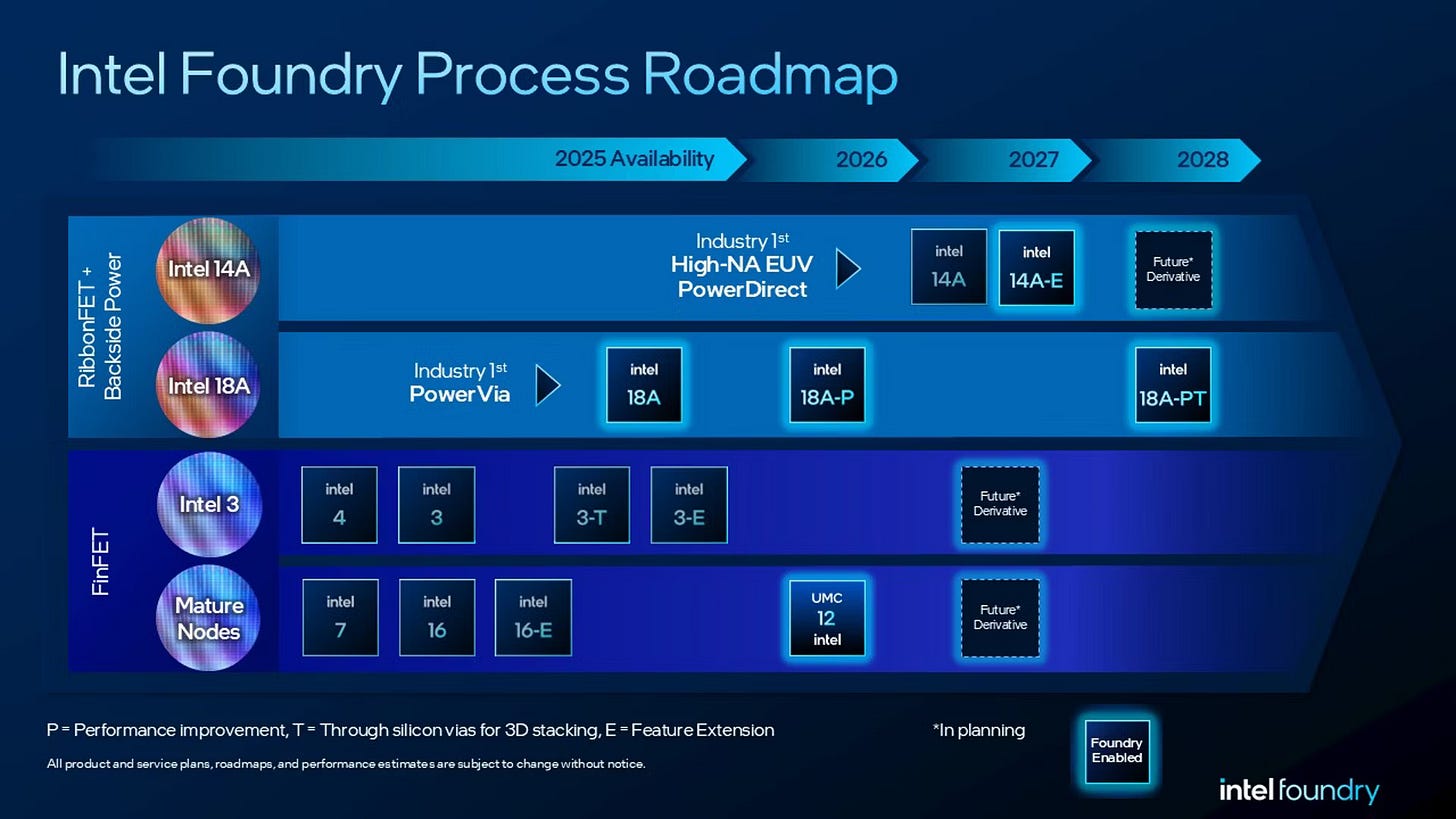

Fast forward. So, where does Intel stand in the foundry business today? There are three main components here: 1) The health of Intel’s foundry unit, called IFS; b) The status of Intel’s process technology portfolio; and c) Fab status (See below for Intel’s process roadmap).

Regarding the fab status, Intel’s newest chip fabrication site in Arizona is expected to begin high-volume production later this year, featuring the most advanced semiconductor manufacturing process technology on U.S. soil.

That’s the good news. The bad news is that IFS continues to struggle and lose money. IFS is unable to secure any large-scale foundry customers.

In addition, Intel’s 18A process won’t help matters. As it turns out, 18A isn’t a mainstream foundry process. Most, if not all, foundry customers aren’t interested in the technology. Generally, Intel’s 18A is a manufacturing process that is optimized for the company’s own chips. Even then, Intel is having yield issues with the process.

For the mainstream foundry market, Intel has talked about developing a derivative of 18A. But Intel’s foundry hopes revolves around the development of a next-generation process, dubbed 14A.

14A looks attractive, but there are three issues here. First, 14A won’t be ready until 2027. Second, not all foundry customers want backside power delivery. It’s overkill and expensive for mobile products.

Third, Intel is wishy-washy about 14A. On one hand, the company is promoting the technology. On the other hand, Intel says that it may pull the plug on 14A, if it can’t obtain enough foundry business for the process. Intel’s ambivalence towards 14A doesn’t exude a lot of confidence in the foundry customer base.

To be sure, though, there is room for IFS in the foundry market. But it must overcome several issues and challenges. IFS must find a way to change its negative perception and gain some trust among foundry customers. It also needs to secure some large foundry orders and make money.

Here are some possible ideas and solutions for IFS: 1) Get 14A ready by 2026, not 2027; 3) Develop a 14A derivative without backside power delivery; 3) Develop more mature processes for foundry customers. Mature processes are still in demand; and 4) Monetize the advanced packaging business.

Intel’s foundry roadmap Source: Intel

Monetize the advance packaging business

Packaging is an important part of the semiconductor industry. A package is a small enclosure that protects a chip from harsh operating conditions. A package helps boost the performance of a chip.

More importantly, the future of the semiconductor industry revolves around advanced packaging and chiplets.

Intel has a solid advanced packaging portfolio. In fact, the company is ranked as the world’s largest vendor in terms of advanced packaging revenues in 2024, according to the Yole Group. In the rankings, Amkor is second, followed by ASE, TSMC and others.

Most of Intel’s packaging revenues are derived from its own in-house products. The company also provides packaging and test services for outside customers. The challenge for Intel is to find a way to better monetize its packaging business.

Here are some possible ideas and solutions for Intel: 1) Form a new advanced packaging subsidiary and give it some autonomy; 2) Develop a more viable alternative to TSMC’s popular CoWoS packaging technology; and 3) Intel needs to speed up its chiplet strategy.

Stay the course or go fabless

For some time, there has been a debate in the media whether Intel should keep its fabs or go fabless. It makes for good reading.

But at some point in the future, Intel’s board will likely need to make a difficult decision about the overall structure of the company. This involves three possible future scenarios for Intel: 1) Maintain the status quo; 2) Go fabless; or 3) Take a hybrid approach.

Here's a brief explanation of these scenarios, and the pros and cons of each one:

Maintain the status quo

In other words, Intel will continue to operate “as is” for the foreseeable future. It will continue to design chips. It will continue to make those chips in its own fabs. And it will continue to compete in the foundry business.

Intel has always owned fabs. It makes sense to have design and manufacturing under the same roof. So why change?

The problem? The current strategy isn’t working. Intel’s foundry unit continues to drag down the company. IFS is losing money and it’s unclear when it will become profitable.

Needless to say, Intel needs to quickly turn IFS, if not the entire company, around. Otherwise, Intel is facing a possible and shocking scenario—a bankruptcy filing.

The chances of going Chapter 11 are remote. Still, the Trump administration may need to step in and convince (or force) Apple, Nvidia and others to shift a percentage of their foundry production from TSMC to Intel. Ultimately, the U.S. government may need to bail out Intel. Otherwise, it could disappear.

Go fabless

Here’s another possible future scenario: Intel may need to follow AMD’s strategy. Several years ago, AMD had fabs. But AMD struggled to keep up in the process technology race. So, AMD sold its fabs and went fabless. (AMD’s manufacturing unit was eventually turned into a new and independent foundry company called GlobalFoundries.)

By going fabless, AMD could focus on what it does best—designing competitive chips. The strategy is working. AMD is designing and selling competitive chips. For its leading-edge manufacturing needs, AMD relies on TSMC.

Intel’s specialty is also designing chips. It’s painfully clear that Intel’s foundry unit is a drain on resources. So one possible solution for Intel is to sell the foundry unit and the fabs.

The argument against this scenario is that Intel needs to keep the fabs for competitive purposes. There are also some national security implications. The other downside is that it’s unclear which entity would buy Intel’s fabs and foundry unit. There is a risk that these operations could disappear over time.

Hybrid approach

In my opinion, Intel should seriously look at a third option. It’s a hybrid approach. Intel will continue to design and sell processors and other chips. But it would spin off its fabs and foundry unit. It would form a joint fab/foundry venture with another entity or a consortium. Intel would have a 49% or so stake in the JV.

It’s the best of both worlds for Intel. Another entity runs the foundry unit and fabs. Intel has access to fab capacity. But it’s also unclear if that scenario would work.

Conclusion

Needless to say, Intel is an important company. But to be sure, the company is in a precarious position. Some blame the board for Intel’s missteps. There are many others to blame as well.

Hopefully, Tan has the right formula to revive the company. Otherwise, Intel will continue on its downward spiral. It’s difficult to watch the rise and fall of a semiconductor giant.